As a self-proclaimed student of shame, I’ve collected many personal stories over the years that capture my own battles with it. On one occasion, I was asked to speak about a program I co-created but completely blanked on what I prepared to talk about. Standing there in the park, in front of fellow activists and organizers, I felt frozen – incredibly sweaty, heart pounding, stomach in knots. I just wanted to crawl under a rock and hide. And I felt like that for months after the event, unable to recall it without recoiling into myself and wanting to disappear forever.

With shame being such a dreadful experience, a natural reaction to it is to treat it like a weed. To get rid of it. We try to do this by being better – working out more, making more money, being more put-together. We try to remove the qualities about ourselves that we feel lead to it, hiding our disgraced parts, our shadows, our imperfections. Just look at the multi-trillion dollar wellness industry, and you’ll see how much we invest in trying to rid ourselves of shame..

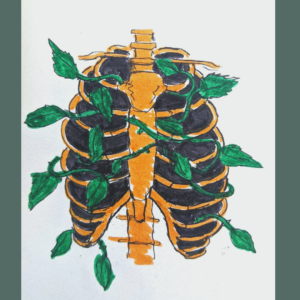

Yet, much like the invasive morning glory plant or non-native blackberry bush, shame is persistent. No matter how much we try to pull it out of our lives, it pops back up in another place or in another form. So, what is shame really, and why is it here? And is it possible that it serves a purpose? Is there something it can teach us?

What is Shame?

Shame is thought to be the deep, painful feeling that there is something wrong with you, that you’re inherently broken. Secretive, it thrives in the shadows. When I work with clients and ask them how they felt about a particularly difficult situation, shame is almost never the first thing that comes up. Yet, they identify with it once I suggest its presence, and it ends up being intricately laced in the experience, hiding in plain sight. It’s almost as if acknowledging the belief that there is something broken about you is too much to bare, on a conscious level.

Shame is often mixed up or mistaken for the word “guilt,” which is the feeling that you did something wrong. This seemingly minor variation has a major impact. It can feel easier to work with guilt, to fix something wrong outside of yourself rather than who you are as a person. Guilt can even help with self-accountability, leaving us with a tinge of pain that helps us adjust our behaviors for the next time. Guilt helps us meet the rules and needs of our community and our need to stay connected to it.

But with shame, we shut down. We feel the inescapable weight that there is something seriously wrong with us, and that we are worthless. This is especially the case when we have made repeated mistakes. This entangled experience can feel a lot more daunting to deal with. Rather than being a motivator, shame can cause us to feel more stuck – how can you change something that might be a part of you?

Starting us at early age, people use shame as a tool to shape us into the type of people they want us to be – to make their lives easier or to help us “fit in.” We were given messages that there was something wrong with who we were, inherently (messy, needy, emotional, childish), that we were bad or too much. After years of these messages, we started to internalize them in the echo chamber of our minds – we started to do that work on ourselves. With pains or fears of punishment or abandonment, shame locks us into place. And it prevents any real growth or expression from happening. Seeds of doubtful, despairing thoughts are sown into our daily encounters, and thrive.

Purposes of Shame

Notice what the body wants to do when you feel or think about shame. Is there a yearn to cave in, to hide, to run away? Is there a sense of anger and defensiveness? Perhaps you feel sick to our stomach and paralyzed. Sound familiar? These mechanisms mirror the classic survival responses that preserve the self in times of perceived danger – flight, fight, and freeze.

In some ways, shame works to protect us when we feel threatened. It protects us from becoming (re)abandoned by our loved ones, by society. It helps us hide the parts of ourselves that we feel won’t be accepted, so we can keep our connections and maintain a sense of safety or belonging.

It just comes at the cost of our authenticity and self-expression. Instead of an opportunity to hold our sense of self while accommodating in relationships, shame shuts us down and shuts us away. In doing so, it crystallizes unwanted behaviors or patterns, hides parts of ourselves that may actually have room to exist, and prevents us from growing.

We can now consider that shame is born out of a very real place of needing one another to survive, and from fears that our imperfections will push people away. It also likely comes from a place of having been abandoned because of these qualities, imperfections or behaviors in the past. As such, shame has served a purpose in finding and maintaining connections, or social security.

We can honor this, and also realize it no longer serves us – at least not in this particular form. With a sense of the purpose of what shame is, where it is from and why it’s here, we can use it to reground, return to ourselves and move towards healthy change.

Composting, Repurposing Shame

Shame may never fully go away. Just like sadness or anxiety, some things return or recur. However, we can continue to work with it, and take the lessons and opportunities as they come. Here are some ways to work with shame:

- When shame stories or feelings pop up, you can just label them as “shame” without judgment, and take the moment to find groundedness. Take some deep breaths, ground into the weight of your body in your chair or your feet on the floor. Create some spaciousness from this shame story.

- See if you can follow shame to the root – and offer yourself kindness and compassion. Maybe there is an old wound here, maybe it’s tied to past experiences of being abandoned or betrayed. (How would you talk to a young person who was feeling this way? What comfort would you offer them? Food, warmth, kind words, a listening ear?)

- For behaviors that others are requesting us to change, with this newfound spaciousness, we can evaluate whether changing the behavior is something aligned with our values.

- If changing the behavior feels right, we can prune these parts down as we would with a tree – just be sure it is not so much that it causes us to abandon ourselves.

- If changing the behavior doesn’t align with our values, we can search for another place that aligns with our values.

- Ask yourself: what parts are meant to stay, that which were never meant to be fully hidden? What of your imperfect parts? Your messy parts? Your childish parts? These are often deeply connected to our joy and creativity and important for your wholeness. Can we invite them back in, in safe-enough settings?

Wrapping Up Shame

As students of shame, we can appreciate it for what it has done to help us survive. We can follow the tendrils down to the root and offer a salve. And we can adjust our branches so they are not encroaching on our beloveds.

Maybe we will remove the parts of shame and plant something else there. Maybe we will make room for something else to grow. As we maintain and admire our essential parts, including our recurring shame and the messages it brings, we can explore and share our unique nature. We can discover how all of our parts fit into the greater social ecosystem, and perhaps one day celebrate this diversity.